[Quick reminder that posts (photos and videos) are better viewed on a web browser and to do so you simply need to click the title of this post.]

Hello everyone,

I'm excited to share another Big Trip blog post with you. It's hard to believe that Shannon and I have been on the road for about eight months now—and in case you had any doubts, we're still absolutely loving every minute of it!

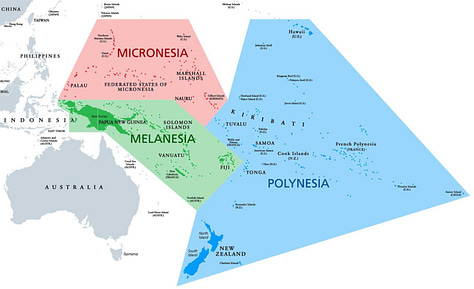

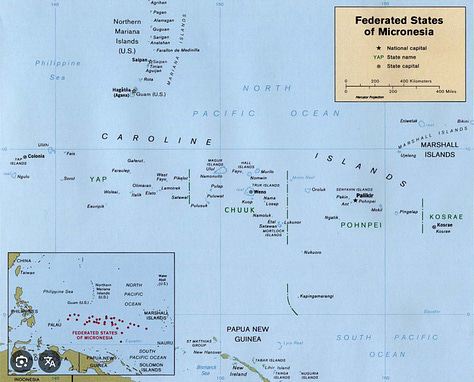

We recently wrapped up a three-week island-hopping tour of the Micronesian region, which included visits to the countries of Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), as well as the U.S. territory of Guam—a trip totalling five distinct island destinations. I’ve attached a few helpful maps for your reference:

Now, these places may not be your typical travel destinations (especially for us Canadians) and I’m sure at least some of you have either never heard of them or only vaguely recall their names. That gives me the fun—yet formidable—challenge of introducing you to these fascinating and remote corners of the world! In doing so, I’ll try my best to weave our personal experiences with some of the region's rich and complex history. This post will be on the longer side and so for those with short attention spans or who might be in a rush, I made a point of using a lot of subheadings so you can jump to the areas that might pique your interest.

And with that, come along for a little tour of Micronesia!

Palau 🇵🇼

We flew 1,000 km east of the Philippines to Palau (population 17,500), our first stop in this Micronesian chapter. In a way, the Republic of Palau was the impetus for us visiting this region in the first place. My fascination with Palau began after I wrote a comparative constitutional law paper while on exchange in Budapest in 2018. The professor said that we could pick any three countries to compare, and being a bit of a smartass, I chose some very random ones…Palau being one of them!

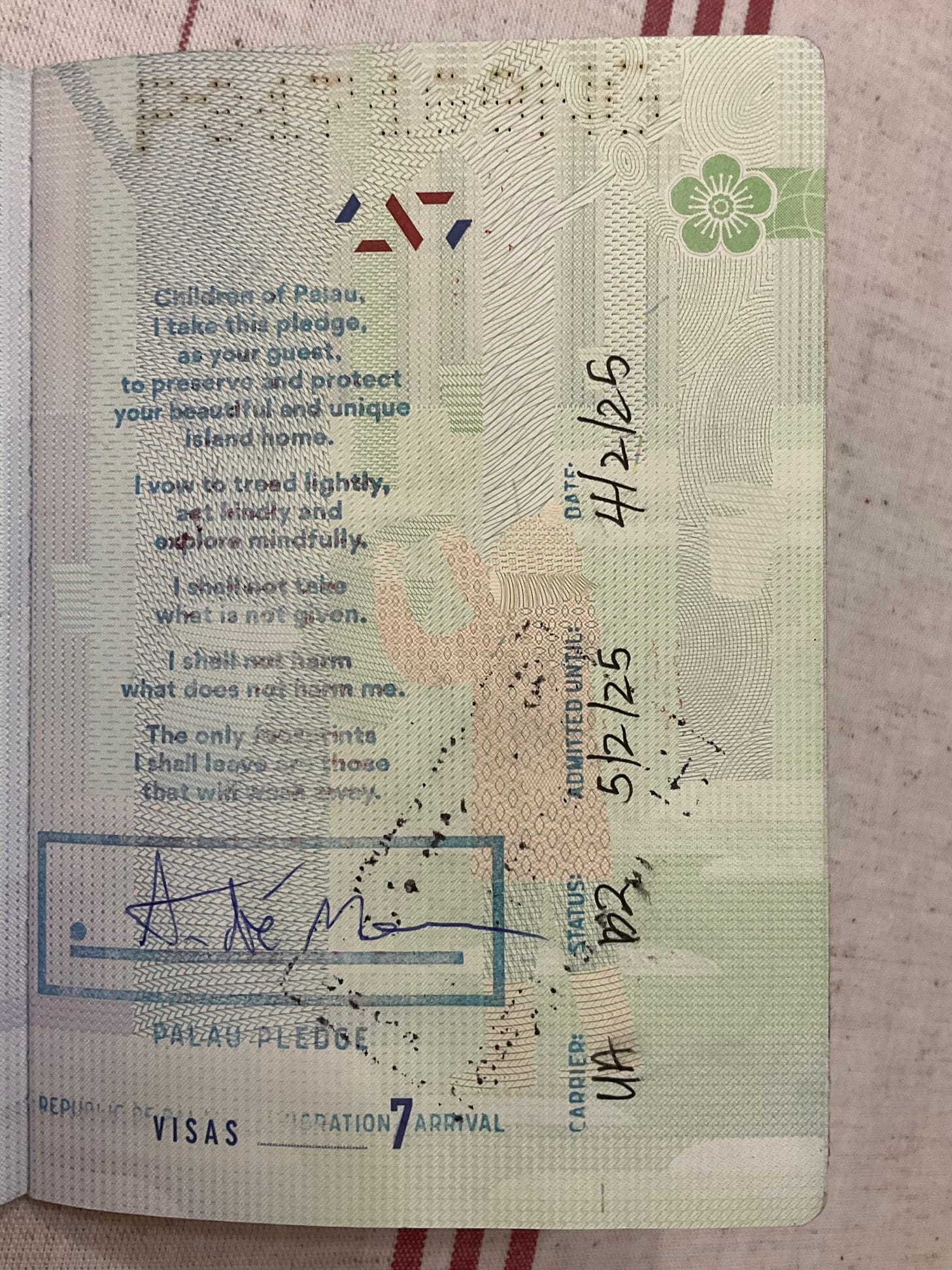

Because of that school assignment, I learned about Palau’s commitment to environmental stewardship and preserving indigenous customs (or “traditional rights,” as referred to in their constitution).

It wasn’t long after landing in Palau that I saw these values materialize—literally—when I got stamped into the country:

To better understand Palau’s identity today, I think it would be useful to first look back on the history and the influence that various foreign powers have had over Palau and Palauans.

A Brief History of Palau

Over the last 250 years or so, control over many of Micronesia’s islands—including Palau—has changed hands several times among colonial powers.

First, Spain claimed Palau in 1686, bibles and crucifixes in hand, but didn’t seriously exert control until 1885. Its most lasting contributions were Christianity and early attempts to alphabetize the Palauan language.

In 1899, Germany bought many Pacific islands, including Palau, from Spain (which was preoccupied at the time with the Spanish-American War). Ever the industrious types, the Germans dredged and blew up land, shoals, and reefs to improve navigation. They also discovered and began mining and exporting phosphate and bauxite. Sadly, early colonization brought diseases like smallpox, which led to the deaths of many Palauans. The Germans did eventually try to contain these outbreaks by providing immunizations.

German control abruptly ended with the onset of World War I, as they refocused their efforts on Europe. Japan quickly swept in and took over in 1914.

The Japanese occupied Palau until 1919, and after the Treaty of Versailles, their rule was officially recognized by the international community. Japan’s influence on Palau was significant: they invested heavily in infrastructure and the economy; pineapple plantations, commercial fishing, and expanded mining operations flourished. Many Japanese also immigrated to Palau during this period and Koror (the largest city) became the administrative centre for Japan’s Pacific operations.1

During this time, Palauans were considered subjects of the Japanese Empire and were forced to learn and speak Japanese. Despite these assimilation efforts, many Palauans still regard the Japanese interwar period quite favourably.

Following Japan’s surrender in WWII, the U.S. began administering Micronesia under a United Nations Trust, essentially making the U.S. the caretaker of Palau until its future—independence, statehood, or otherwise—was decided.

In 1978, Palau chose to separate from the other states of Micronesia and chart its own course. In order to do so, Palau would need to sign a Compact of Free Association with the United States (this is basically an agreement where Palau receives economic aid, defence guarantees, and other benefits from the United States in return for granting strategic access and cooperation on certain policies — mainly defence-related).

In Palau's case, ratifying the Compact took much longer than its Micronesian neighbours (the FSM and the Marshall Islands). This was because its draft constitution included an anti-nuclear clause prohibiting nuclear weapons, which it is said to be the first constitution in the world to do so. The U.S. refused to sign on since these provisions would prevent American nuclear-powered ships (or weapons) from entering Palau’s waters and ports. After 13 years and seven plebiscites, however, Palau officially became its own country in 1994—making it the last post-WWII UN Trust Territory to do so.

Our Experience in Palau

We spent five days in Palau, two of which were dedicated to scuba diving in some of the most pristine waters and coral reefs we've ever seen. Unfortunately for you, dear readers, no one in our group had a fancy underwater camera to document the incredible fish and (many!) sharks we swam with. But the boat rides to the dive sites were also stunning:

One of our first stops on our first morning in Palau was the Koror Jail. You might think that visiting a jail is an odd way to kick off a tropical vacation—and you'd be right!

The reason for this visit is that we had learned that the some of the inmates (of which there are about 86 total) participate in a restorative justice program where they create traditional handicrafts. This program helps inmates to develop skills, reconnect with their culture, and earn some money. It reminded us of a similar initiative in Nunavut, where inmates at the Iqaluit jail carve soapstone or make traditional clothing.

At the Koror Jail, inmates carve “storyboards” out of mahogany—beautiful, intricate pieces that depict Palauan legends and oral histories. A big, friendly Palauan man named Shmart (no older than 40), who is currently serving time, came out to show us the storyboards and explain some of the tales. It was a unique and memorable experience. We ended up buying a storyboard that tells the legend of Tulei and Surech—a kind of Palauan Romeo and Juliet.

Throughout our stay, we were based in Palau’s largest "city," Koror, which has a decent selection of shops, hotels, and restaurants. Every other Friday, Koror hosts a community night market featuring food stalls, handmade crafts, and live performances from local high school students. Our favorite dish? Fried shredded taro in coconut milk served with rice, which was made by some of the ladies from the Palau High School Class of 1981. Delicious!

The market was such a wholesome, lovely experience. It gave us a great glimpse into the local community while also serving up a variety of cheap and tasty bites.

Our final days in Palau were spent road-tripping around the main (and largest) island. You can drive the full loop in under half a day but we stretched it over two days to take in the sights.

We visited Palau’s capital, Ngerulmud, to check out the Parliament and Supreme Court buildings. Sadly, our visit landed on a weekend, so we couldn’t get a tour inside the buildings.

We also took in the viewpoints, waterfalls, and colourfully decorated men’s meeting houses known as bai. These buildings were traditionally used by men to discuss all sorts of community matters but it’s worth noting that Palau (like FSM) is a matriarchal society and land ownership is passed down through women (how refreshing)!

The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) 🇫🇲

After Palau, we visited three of the four states of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM): Yap, Pohnpei, and Chuuk.2 Each state is distinct, with its own unique culture, language, and ethnicity. Because of this, I got the sense that FSM is more of a political rather than a cultural construct: people in FSM seemed to identify themselves first and foremost as being Yapese, Pohnpeian, or Chuukese rather than as a citizen of FSM. This perhaps has to do with the vast distances between the states.

For reference, the FSM has a population of about 100,000 spread across 607 islands, spanning over 3,000 km and two time zones. Thus, it’s no wonder that a Yapese person might feel more in common with someone from Palau, which is geographically closer to Yap than the rest of the FSM states.

Another reason for the lack of national cohesion in the FSM could be that there are barely any direct flights between the FSM’s islands. Travel often requires taking expensive flights from one of the country’s four major airports, typically connecting through Guam. United Airlines (an American airline) is the only commercial airline that operates in the region, which keeps costs high and flight schedules based on cost-saving, not convenience (many of the flights to/from these Pacific islands leave late at night/early in the morning, which made travelling around this region rather unpleasant).

I couldn’t help but notice how similar this transportation challenge is to Nunavut, where 25 remote communities—spread across a vast territory and three time zones—rely on expensive flights operated by a single airline (Canadian North), usually connecting through Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, or Yellowknife.

This would be just one of several parallels with the Canadian Arctic that I’d come to notice during my time in the region.

Yap

Yap was the first FSM state that we visited. It has a reputation for being the most traditional of the four states. For example, despite having elected officials, it is still the village chiefs that hold much of the political power within the communities.

Until just 15–20 years ago, men donned only loincloths and women went about their lives topless. We heard anecdotes that this traditional way of life still exists on Yap’s outer islands, just as it has for hundreds of years, but in Colonia (the state capital where we stayed) men now wear shorts and women cover their bosoms.

Yap is also famous for its giant stone money—called rai in Yapese—a currency that can weigh several hundred pounds! While the U.S. dollar is the official currency in the FSM, rai stones are still occasionally used in Yap for ceremonial or symbolic exchanges.

The story goes that in the year 1500 AD, two seafaring navigators—Anagumang and Fathan— came across beautiful stone cliffs in what is now Palau. They quarried a piece of stone and brought it back to Yap, where such stone doesn't naturally occur. The locals were quite impressed and thus the tradition of stone money was born.

Carving these stones could take years, as the Yapese would only use basic tools made from shells, wood, or other stones (at least initially). The stones were then hauled on bamboo rafts towed behind dugout canoes, sailing across hundreds of kilometres of open ocean back to Yap.

The value of a rai stone depended on its material, shape, size, and the difficulty of the journey and tools used to bring it home.

Although quarrying (and the perilous boat trips) stopped around the early 20th century, more than 6,000 rai stones are still scattered across Yap, serving as a cultural symbol and immense source of pride for the Yapese.

During our four days on Yap, we spent three of them scuba diving. We had a great time exploring the marine life both on and off the boat—lots of sharks again!

I especially enjoyed getting to know our captain and dive master, both of whom were from smaller outer islands in Yap. When prompted, they shared many stories and anecdotes. For example, the captain has worked at the dive resort for over 30 years and logged about 25,000 dives (!!!). He’s from the remote island of Satawal, which takes two weeks to reach from Colonia via a slow island-hopping cargo ship (though tickets are only $30 USD!). He’s retiring in May 2025 and was very excited to return home.

Another thing that quickly stands out in Yap is the widespread chewing of betel nut. Yapese people love the stuff. The nut comes from a palm tree and is chewed for its stimulating effects. On Yap, it’s often mixed with dried lime powder and/or cigarette tobacco, then wrapped in the leaf of a pepper tree. It stains the teeth orange, so many Yapese have bright orange-brown smiles. What’s more, everyone seems to carry their betel nut kit in these hand-woven purses. When asked why they carry them in the woven purses, the dive master simply answered “it’s tradition”.

On our final day in Yap, Shannon and I rented a car and spent a quick three hours driving around the contour of the island. We visited some stone money banks, WWII wreckage, and more traditional men’s meeting houses—called faluw in Yapese.

Pohnpei

Our second stop in the FSM was Pohnpei, the largest state by area and home to the nation’s capital. Pohnpei is often regarded as the most developed and westernized of the FSM states. The biggest city is Kolonia (not to be confused with Colonia in Yap), while FSM’s capital, Palikir, is about a 20-minute drive inland.

FSM’s capital is modest—it consists of a dozen or so government buildings, including Congress and the Supreme Court, and not much else (not even a hotel or restaurant!).

At the visitor centre, we learned that Pohnpei receives roughly 1,000 tourists a year—about the same number that the Italian Pompeii receives every three hours. Apparently, many of these visitors are surfers, as the nearby shoals offer world-class waves.

Our time in Pohnpei didn’t involve any surfing or diving (though we hear the dive sites are also quite good) but instead focused on hiking and exploring the island’s dense, lush forests. Pohnpei is one of the wettest places on Earth, receiving an average of 4,775 mm of rainfall annually along the coast and 7,600 mm in the mountains. Luckily for us, the rain came in short, manageable spurts.

One of the highlights of Pohnpei was the “Six Waterfall Hike,” a pretty intense jungle trek that passes by six lovely waterfalls. While the elevation wasn’t too bad, the rocky terrain was incredibly slick—it felt like we could slip and fall with every step. Still, the hike was stunning and we swam at every waterfall, which was a perfect way to cool off from the muggy heat. We didn’t see another soul during the entire six-hour hike, which didn’t surprise us after our 63-year-old guide, Welten, said it had been over two months since he last took anyone on the trail. This seemed pretty accurate as Welten was busy clearing the path with his rusty machete as we traversed the overgrown trail!

Before catching our flight out of Pohnpei, we hiked along Sokeh’s Ridge, a mountain ridge outside of Kolonia where several rusty WWII Japanese relics still remain fairly intact. The ridge also offered incredible views of Pohnpei’s coastline and as a bonus, we spotted the beautiful Pohnpei Lorikeet, a maroon-coloured parrot found only on this island!

Chuuk

Our third and final stop in the FSM was Chuuk, the country’s most populous state that is known for being the roughest and least prosperous region in the FSM. The unemployment rate is about 40% and there's a high dropout rate among high school students, contributing to a relatively high crime rate. Before visiting and while on the island, many people advised us not to go out at night “because it’s dangerous.” Chuuk also faces pollution problems, with inadequate sewage treatment and litter strewn all over the island (not exactly a Pacific paradise but since our flight stopped over there anyway, we figured we’d check it out for ourselves!).

Speaking of waste collection… we couldn’t help but notice the hundreds (if not thousands) of cars abandoned on the side of the road, both in Pohnpei and Chuuk. It seems that these islands have no means or policies in place to dispose of their old vehicles. Given the tropical climate, it doesn’t take long for the vegetation to take over and envelop the cars, consuming them into the bushes and forests.

Despite these challenges, the main draw for the approximately 7,000 tourists that Chuuk receives a year is the impressive collection of 60+ sunken WWII Japanese ships and 250 airplanes that lie in the surrounding lagoon.

As a quick background, Chuuk Lagoon was where Japan harboured many of its ships during the war. After Pearl Harbour, it took the Americans a bit of searching to figure out where Japan‘s ships were located; once they figured it out, the Americans conducted Operation Hailstone, a major air assault in February 1944 that resulted in the largest naval loss in history. The aftermath of this assault remains scattered along the lagoon's floor.

Given that we were in the best place in the world for wreck diving, we decided to try it out — a first for both of us. As a history enthusiast, this was something I was keen on experiencing, whereas Shannon was a little less interested in the idea but went along with it anyway.

Our diving experience involved dives to two sites: the first was the Heian Maru (163 meters long), a Japanese ocean liner cargo ship that was requisitioned as a submarine depot ship; the second was the Fujikawa Maru (133 meters long), a refrigerated cargo ship converted to transport military supplies and aircraft.

Despite being in such a historically significant place and having the once in a lifetime opportunity to visit these wrecks, unfortunately our experience was less than ideal. First, we received pretty much no briefings on the ships nor the routes we’d be taking on our dives. All the ship information that you read in the previous paragraph was the result of research that we pieced together after the dives, which meant that we couldn’t totally appreciate what we were looking at when we were down there. Second, it was the first time we felt unsafe while diving. There were eight divers with various levels of experience and only one dive master. In open water or along coral reefs, this isn’t a huge issue but when you’re navigating dark, narrow, maze-like corridors of a rusty ship, it’s just dangerous. Case in point: at one point, Shannon and another diver lost the group while in the ship and for a few scary minutes they did not know how to exit the wreck… thankfully they found a way out but you can imagine how terrifying that would be, especially 25 meters below the surface.

After this experience, we were a bit "dived out" and spent the remaining day and a half in Chuuk relaxing at our expensive and quite dingy hotel (another similarity to the Canadian Arctic: hotels tend to be extremely pricey for the quality of accommodation and service that you receive).

While Chuuk may be a very remote place, we had a very small-world encounter on our final day there when we ran into a group of Canadians from southeastern Ontario who had just finished a scuba diving liveaboard around Chuuk — one of them even knew someone from Penetanguishene (a Moreau no less!). A couple of them joined us one afternoon to visit a(nother) Japanese war gun tucked away in the nearby mountains. It was neat to see the dugout tunnels and the vantage point that Japanese had overlooking the lagoon. It was surprising for us that, when looking at the mountain afterwards, we could not even guess at where the gun was located: it was that camouflaged within the mountainside.

Guam 🇬🇺

The unincorporated American territory of Guam was a whole other world compared to the rest of the Pacific islands that we visited. First of all, almost immediately I noticed that Guam had a very different topography consisting of savannah, forest, and sandy beaches (which was a contrast from the mangrove coastlines of FSM and Palau). The wide array of free public beaches was a pleasant surprise as we had several occasions where we needed to kill time on Guam during lengthy layovers — and what better place to do so than on a beach?

However, we couldn't help but feel a bit guilty to be on U.S. soil given the nonsense coming from Washington; we just had to remind ourselves that we booked our flights well before this tariff/51st state stuff started and that Guamanians cannot vote for the US president. As a small act of resistance (or maybe just humour), we decided to only listen to Canadian music while driving around Guam in our rental car.

A Brief History of Guam

Guam’s history, as we came to learn, is layered and fascinating. Archaeological records show that the Chamorro people—Guam’s Indigenous population—have inhabited the island since at least 1500 BC. Like many islands in the Micronesian region, Guam saw the arrival of Spanish colonizers, who introduced Christianity and claimed dominion over the land.

In 1898, Spain “sold” Guam to the United States, part of the same deal that included the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Unlike Micronesia and Palau, where some forms of traditional land ownership still survive, Guam saw those systems all but eradicated under U.S. rule. Through unjust taxation policies, many Chamorro families were pushed into debt which eventually and inevitably forced Chamorro families to give up their land to the U.S. Navy administration.

Then came WWII. Japan occupied Guam for 32 months, beginning in December 1941 (just after Pearl Harbor). During this time, islanders lived under martial law and were subjected to harsh conditions and forced labor to support the Japanese war effort. By 1942, Japan had expanded its empire across the Pacific—from China to Burma to Papua New Guinea—and Guam was firmly caught in the crossfire.

In July 1944, the U.S. launched a massive assault to retake the island. The Battle of Guam was devastating: over 25,000 lives were lost during a relentless 13-day bombardment. After the dust settled, the U.S. reclaimed Guam—but not without consequence. The land, the people, and the memory of the island were permanently altered.

After the war, the U.S. seized 63% of Guam’s land. Today, the U.S. Department of Defense still controls 28% of the island and many Chamorro families remain locked in disputes over land that was expropriated from them more than a century ago. And yet Guamanians also have one of the highest per-capita recruitment rates in the U.S. military — a detail that’s as ironic as it is sobering. That being said, while Guam might be “US soil,” it really felt as though Guam’s story is entirely its own.

Our Experience in Guam

We spent a considerable amount of time in Guam given that we had a few layovers there and so we got a pretty good feel for the island. Some of our time was spent at the beach, relaxing and getting a tan (or at least trying to not get a sunburn) and other days we drove around and explored the entirety of the island.

We did some nice hikes, explored and swam in Pagat cave, and visited a couple of museums to learn more about the history (which we don’t learn much about in Canada). Overall, I enjoyed Guam more than I thought I would — and I especially enjoyed that many of the activities we wanted to do were free or at a negligible cost, especially given that Guam is quite an expensive island!

Speaking of costs, I should also note that the reason we were even able to get to these prohibitively expensive remote Pacific islands is thanks to the frequent flyer points that we’d amassed over the years, which we applied to the United Airlines flights. Otherwise, the many island hopping flights that we took in this far-flung part of the world would have cost us almost $5,000 CAD each!

Thank you for reading along and I really hope you were able to get a better sense of what our travels were like in this part of the world while also learning a little about the culture, history and diversity of the Micronesian region!

Until next time!

André

PS: We always welcome comments and questions so feel free to leave us a note!

Random aside: Japanese scientists working in Palau were the first to discover that coral can absorb nutrients via photosynthesis—something that's common knowledge now.

Kosrae is the fourth state, which we unfortunately didn’t get to visit.

Oh wow, this all sounds amazing, Palau especially! The diving all looks incredible too!!

Incredible! I learned so much from this post - Yap’s stone currency is fascinating.

The quiet of Micronesia must have felt like whiplash compared to the crowds and tourist traps of the Philippines!!

How do you guys plan on sending that gorgeous story board home?